I kada su se osvrnuli unazad, videli su svoju budućnost…

G. Gospodinov, Vremensko sklonište

Dugi niz godina, čak decenija, Vladimir Perić Talent gradi svoje vizuelne iskaze od nađenih, starih, odbačenih predmeta koji su izgubili svoju upotrebnu funkciju, čija je i sentimentalna vrednost zatrpana naslagama novih tehnoloških pomagala, potrošačkih navika i potrošenih života. Pronalazi ih na buvljim pijacama i otpadima, sakuplja ih i čuva, povezuje, proučava i izlaže. U visokorazvijenom tehnološkom univerzumu digitalne kulture, na pragu AI civilizacije, ovi predmeti se vraćaju u život i vraćaju nas u neko prošlo, zaboravljeno vreme ispunjeno fragmentima nepovezanih, lagodnih, gotovo utopističkih sećanja, kada je svet bio naseljen albumima sa sličicama, Miki Mausima, školskim priborom, lektirama, fotografijama na papiru i kasicama (Muzej detinjstva, 2006-2016, work in progress).

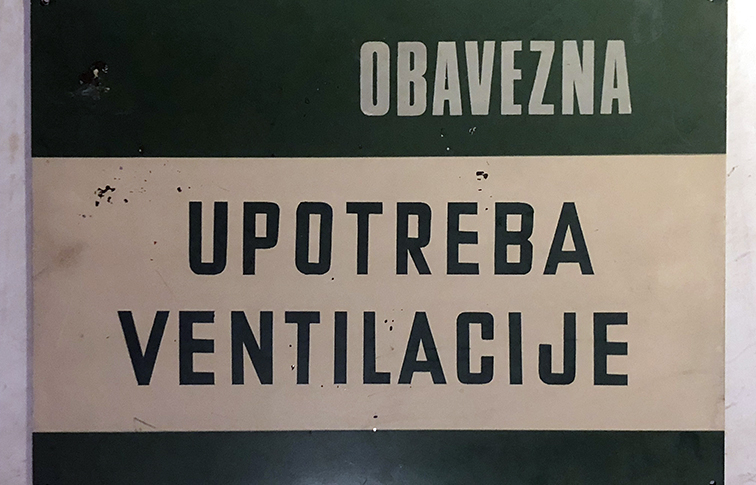

Ovaj put, međutim, nije reč o snolikom svetu detinjstva, ispunjenog crno-belim fotografijama i nostalgijom, već o porukama. Izložba Namenjeno-zamenjeno sastoji se od dve serije radova u formi poruka upozorenja-podsećanja-zabrana. Tekst tih poruka ilustrovan je jednostavnim crtežima, najčešće svedenih na znak. Jednu grupu radova čine sigurnosna upozorenja namenjena-preuzeta iz fabrika i industrijskog konteksta. U pitanju su aluminijumske ploče na kojima su grafički – povezivanjem slike i teksta – predstavljena upozorenja koja, direktno i neposredno, prenose poruke o potencijalnim izvorima opasnosti. Tu su ona poznata, i danas, upozorenja koja se tiču lične, ali i kolektivne sigurnosti kao što su: Zabranjeno pušenje, Opasnost od požara, Opasnost od električne energije, Zabranjen ulaz, Zaštiti telo pri radu… Ima, međutim, i složenijih rešenja. Neka od njih uključuju i određeni ideološki okvir – Drugovi, zaštita na radu je vaše pravo, obaveza, odgovornost – ili imperativ – Pušenje nije samo štetno, već i opasno – ili određene socijalne vrednosti – Čuvajući sebe, čuvaš i porodicu. Može se naći i po koji poetski iskaz – Ništa nije manje od iskre, veće od požara, skuplje od života – ali i sasvim eksplicitna opomena: Ne ubija struja, već tvoj NEMAR…

Posebnu celinu čine radovi iz oblasti filumenije (sakupljanja kutija šibica). Šibice, takođe, pripadaju nekoj dalekoj epohi. Danas su, skoro u potpunosti, nestale iz upotrebe tako što su zamenjene plastičnim upaljačima, a njihovom istiskivanju iz našeg svakodnevnog okruženja doprinelo je i povezivanje sa ultimativno nezdravom navikom. Mnogo pre uvođenja u ovaj negativni kontekst, međutim, šibice su imale, pored svoje bazične i edukativnu funkciju. Na malim površinama kartonskih kutijica nalazile su se, kao i kod sigurnosnih tabli, u kombinaciji slike i teksta, poruke: Trezvenost na radu, garancija sigurnosti na radu, Ne loži vatru u šumi, Ne zagađujte vazduh i vodu, Ne idite putem, opasno po život… Neka od izloženih grafičkih rešenja, uvećana i isprintana na papiru, preuzeta su sa šibica proizvedenih u čuvenoj fabrici Dolac kod Travnika. Osnovana daleke 1901, jedna je od malobrojnih fabrika šibica na Balkanu, pored fabrike Drava, i zapošljavala je preko dvesta radnika. Ona postoji i danas, privatizovana i smanjena na desetak radnika koji se bore “da održe tradiciju i potrošačima ponude domaći proizvod”. Kolekcija sadrži i šibice različitih proizvođača iz regiona, na različitim, uglavnom srednjeevropskim jezicima sličnog sadržaja iz perioda sredine prošlog veka, iz daleke i, istovremeno, bliske prošlosti.

Ta daleka i uvek bliska prošlost je sindrom našeg vremena, o čemu piše i Georgi Gospodinov u Vremenskom skloništu. Prošlost povezuje sve, naizgled, nepovezane događaje, junake, situacije i dešavanja. Ona je utočište, sigurna kuća, opsesija, ideologija, utopija, dijagnoza, politička platforma i strategija za preživljavanje sadašnjosti, jednom rečju, živimo u vremenu epidemije prošlosti! 20. vek je započeo zagledan u budućnost, sa avangardama, futurizmom i konstruktivizmom, sa jasnim slikama budućnosti, tehnološkim estetizmom, arhitektonskim i urbanističkim rešenjima koja će se realizovati tek u drugoj polovini veka. Revolucionarna avangarda je imala za cilj da počisti poslednje ostatke prošlosti, zaparloženih klasicizama, romantičarskih pastorala i klasnim nejednakostima i uvede nas u moderni svet ispunjen mašinama, automobilima i brzinama.

Sredinom veka počinje da dominira sadašnjost, sa novim umetničkim praksama koje uvode dimenziju sadašnjosti u umetnički rad, tako da “sada i ovde” postaje ultimativna dimenzija događajnosti koja, sa pojavom videa, dobija svoju tehnološku potporu. Te nove pokretne slike se, za razliku od filma, odmah prenose, reprodukuju, distribuiraju i edituju. Pamela Li govori o opsednutosti vremenom, pre svega, sadašnjim i strahom od istog, karakterističnim za šezdesete godine proškog veka, kada se sa uvođenjem kompjuterskih tehnologija, privodi kraju proces izlaska iz mašinskog doba. Nastavak procesa ubrzanja ona dovodi u vezu sa nadmetanjem u tehnološkom prvenstvu, čija je glavna manifestacija trka u naoružanju između Istoka i Zapada, koja ubrzo prerasta u trku sa vremenom i počinje da se preliva na ekonomiju, biznis i sve segmente našeg života. Simbolički početak ove trke ona povezuje sa silaskom na Mesec, tehnološkim vrhuncem tog vremena, i svoju knjigu Hronofobija započinjeanalizom fotografije ovog događaja. Izlišno je reći koliko smo – i danas – u toj trci. Ona upravlja logikom našeg života, a dobila je i nove atribute: prolaznost, trenutačnost i propadljivost (Bauman). I kraj joj se ne nazire.

U postpandemijskom svetu, sadašnjost je nestabilna, tenzična, konflikta i krizna, a budućnost neizvesna. Ono što jedino uliva sigurnost i eskapističko olakšanje je prošlost koju stalno oživljavamo preko različitih narativa. Digitalne tehnologije i globalizacija su nas uvele u 21. vek. Tu nas je, međutim, sačekala kriza, tačnije niz kriza koje se nadovezuju, prepliću i postaju konstanta u našim životima. Jedna od njenih manifestacija je kriza narativa, koju prepoznajemo u reaktualizaciji zastarelih, konzervativnih i drugih retrogradnih narativa, koji nas vraćaju u prethodnu paradigmu, podeljeni i hladnoratovski svet. Vođeni inercijom stare logike nasleđene iz prethodnog veka, retronarativi su laki, pitki i ne zahtevaju napor promišljanja. Predstavljaju “idealno” rešenje-za-poneti za nesnalaženje u kompleksnom svetu, beg od novog, različitog i suočavanje sa promenom koja se, želeli mi to ili ne, odigrava. Iskustvo tog prošlog sveta, međutim, čini se da nam uporno izmiče.

Treću deceniju 21. veka Berardi dovodi u vezu sa pojmom uncheimlich (uncanny) za koji kaže da predstavlja duh našeg vremena. Ono što proizvodi ovaj začudni, neugodni osećaj u našim životima je “koegzistencija nekompatibilnih realnosti”, a možemo da je dovedemo u vezu sa već pomenutim kontradikcijama: aproprijacijom sadašnjosti od strane prošlosti, dualnim hladnoratovskim uokviravanjem globalnog umreženog sveta, uvođenjem virtuelne i proširene realnosti (VR, AR, XR) praćene simultanom reaktualizacijom retronarativa. Berardi ovo dovodi u vezu sa fenomenom koji je postao deo naše svakodnevice: sve češće se susrećemo sa inteligentnim mašinama i hiperinteligentnim uređajima i, istovremeno, ljudima koji se sve više ponašaju kao automati, bez inteligencije. Ova kognitivna automatizacija, koja se simultano odvija sa eskalacijom haosa, čini se da ima cilj da pruži privid uređenosti stanju opšte panike u kojem živimo.

I tu se opet vraćamo porukama, edukativnim podsećanjima i sigurnosnim upozorenjima iz prošlosti koje, sada to možemo otvoreno reći, nismo isčitali. Prevideli smo neka prošla znanja, nismo se suočili sa prošlim iskustvima, i prošlost nam se stalno vraća, ali svaki put još strašnija. Šta je to što smo iz prošlosti prevideli? Koja smo to iskustva zaobišli? Na koja upozorenja se nismo obazirali? O koje zabrane smo se oglušili? Kakva upozorenja nismo ispratili? Da li ćemo imati drugu šansu? Vladimir Perić Talent nas suočava sa tim propuštenim prilikama. Kao iskusni dugogodišnji arhivar naše prošlosti, kolekcionar našeg detinjstva, sakupljač fragmenata naše svakodnevice, on nas iz našeg haotičnog, visokorazvijenog tehnološkog sveta digitalne kulture vraća u, naizgled, jednostavnan, uređen svet koji obiluje jednostavnim, direktnim rešenjima kako da izbegnemo opasnost. Da li je izložba Namenjeno-zamenjeno naša “druga šansa”?

Reference

Bauman, Zigmunt, Fluidni život, Mediterran Publishing, Novi Sad 2009.

Berardi, Franco “Bifo”, “Unheimlich: The Spiral of Chaos and the Cognitive Automaton”, e-flux, 2023.

Gospodinov, Georgi, Vremensko sklonište, Geopoetika, Beograd 2023.

Lee, Pamela M., Chronophobia: on Time in the Art of the 1960s, The MIT Press 2004.

Second Chance

And when they looked back, they saw their future…

G. Gospodinov, Time Shelter

For many years, even decades, Vladimir Perić Talent has been building his visual statements from found, old, discarded objects that have lost their utility function, and whose sentimental value is buried beneath layers of new technological aids, consumer habits and spent lives. He discovers them at flea markets and junkyards, collects and preserves them, connects them, studies them and exhibits them. In the highly developed technological universe of digital culture, on the threshold of the AI civilization, these objects come back to life and bring us back to some bygone, forgotten time filled with fragments of disconnected, comfortable, almost utopian memories, when the world was populated with sticker albums, Mickey Mouses, school supplies, school reading books, paper photographs and piggy banks (Museum of Childhood, 2006-2016, work in progress).

This time, however, it’s not about the dreamlike world of childhood, filled with black-and-white photographs and nostalgia, but about messages. The exhibition Namenjeno-zamenjeno [Intended-Replaced] consists of two series of works in the form of warning-reminder-prohibition messages. The text of these messages is illustrated with simple drawings, usually reduced to signs. One group of works consists of safety warnings originally intended for use in/ taken from factories and industrial contexts. These are aluminium plates with graphical representations (combination of images and text) of warnings that directly and straightforwardly convey messages about potential sources of danger. There are those warnings, still familiar today, concerning personal as well as collective safety, such as: No Smoking; Fire Hazard; Danger of Electric Shock; No Entry; Protect Your Body at Work… However, there are also more complex solutions. Some of them involve a certain ideological framework – Comrades, Safety at Work Is Your Right, Obligation, Responsibility – or an imperative – Smoking Is Not Only Harmful, But Also Dangerous – or specific social values – By Protecting Yourself, You Protect Your Family, Too.There are even some poetic statements – Nothing Is Smaller than a Spark, Greater than a Fire, More Precious than Life – but also explicit warnings: It Is Not Electricity That Kills, but Your NEGLIGENCE…

Works in the field of phillumeny (collecting matchboxes) make a separate unit. Matches, too, belong to a bygone era. Today, they have almost entirely disappeared from use, replaced by plastic lighters, and their removal from our everyday surroundings has been influenced by their association with an ultimately unhealthy habit. However, long before being linked to this negative context, matches, in addition to their basic function, had an educational purpose. On the small surfaces of cardboard matchboxes, like on the plates with safety signs, messages were presented through a combination of image and text: Sobriety at Work, Guarantee of Safety at Work; Do Not Start a Fire in the Forest; Do Not Pollute the Air and Water; Do Not Walk on Roadway, Life-Threatening… Some of the exhibited graphic solutions, enlarged and printed on paper, were taken from matches produced at the renowned Dolac factory near Travnik. Founded back in 1901, it is one of the few match factories in the Balkans, besides the Drava factory, and used to employ over two hundred workers. It still exists today, privatized and reduced to some ten workers who strive “to maintain tradition and offer consumers a domestic product”. The collection also includes matches from various manufacturers from the region, in different, mostly Central European languages with similar content from the mid-20th century, from a distant past, yet close to us.

The distant and always close past is a syndrome of our time, which Georgi Gospodinov also writes about in his Time Shelter. The past connects all seemingly unrelated events, heroes, situations and developments. It is a refuge, a safe house, an obsession, an ideology, a utopia, a diagnosis, a political platform and a strategy for surviving the present; in short, we live in a time of an epidemic of the past! The 20th century began looking to the future, with avant-gardes, futurism and constructivism, with clear visions of the future, technological aestheticism, architectural and urban solutions that would only be realized in the second half of the century. The revolutionary avant-garde aimed to sweep away the last remnants of the past, stale classicisms, romantic pastorals and class inequalities, leading us into a modern world filled with machines, cars and speeds.

Around the mid-century, the present began to dominate, with new art practices that introduced the dimension of the present into artworks, making “here and now” the ultimate dimension of eventivity, which, with the appearance of video, got technological support. These new moving images, unlike film, are instantly transmitted, reproduced, distributed and edited. Pamela Lee speaks about the obsession with time, especially the present, and the fear of it, characteristic of the 1960s, when the introduction of computer technologies marked the end of the process of leaving the machine age. She relates the continuation of the acceleration process to the competition for technological supremacy, the main manifestation of which being the arms race between East and West, which soon evolved into a race against time and started extending into the realms of economy, business and all aspects of our lives. She connects the symbolic onset of this race with the landing on the Moon, the technological pinnacle of that time, and begins her book Chronophobia by analysing a photograph of this event. It is needless to say how much we are still – even today –in this race. It governs the logic of our lives, and has acquired new attributes: transience, immediacy and perishability (Bauman). And its end is not in sight.

In the post-pandemic world, the present is unstable, tense, marked by conflict and crisis, and the future is uncertain. The only source of security and escapist relief lies in the past, which we keep reviving through various narratives. Digital technologies and globalization have ushered us into the 21st century. However, upon arrival, we were met with a crisis, or rather a series of crises that build on each other, overlap and become a constant in our lives. One of its manifestations is the crisis of narratives, recognized in reactualization of obsolete, conservative and other retrograde narratives, which propel us back into a previous paradigm, a divided and cold-war world. Driven by the inertia of old logic inherited from the previous century, retro-narratives are easy, smooth and do not require the effort of thoughtful consideration. They represent an “ideal” take-away solution for getting lost in a complex world, an escape from the new, the different, and facing the change that – whether we like it or not – is taking place. However, the experience of that past world seems to persistently elude us.

Berardi associates the third decade of the 21st century with the concept of uncheimlich (uncanny), which he claims represents the spirit of our time. What produces this strange, unsettling feeling in our lives is the “coexistence of incompatible realities”, which can be linked to the already mentioned contradictions: the appropriation of the present by the past, the dual cold-war framing of the globally interconnected world, the introduction of virtual and augmented reality (VR , AR, XR), accompanied by the simultaneous reactualization of retro-narratives. Berardi relates this to a phenomenon that has become part of our everyday life: more and more often we encounter intelligent machines and hyper-intelligent devices and, at the same time, people who behave more and more like automatons, devoid of intelligence. This cognitive automation, which takes place simultaneously with the escalation of chaos, seems to aim at providing an illusion of orderliness to the state of general panic in which we live.

And here we go again with messages, educative reminders and safety warnings from the past that – now we can say it openly – we haven’t read. We have overlooked some past knowledge, we haven’t confronted past experiences, and the past keeps coming back to us, but each time more terrifying. What is it that we’ve overlooked from the past? What experiences have we bypassed? Which warnings have we ignored? What prohibitions have we disregarded? What alerts haven’t we followed? Will we have a second chance? Vladimir Perić Talent confronts us with those missed opportunities. As an experienced, long-time archivist of our past, a collector of our childhood, a gatherer of fragments from our everyday life, he transports us back from our chaotic, highly developed technological world of digital culture to what appears to be simple, organized world that abounds with straightforward, direct solutions on how to avoid danger. Is the exhibition Namenjeno-zamenjeno our “second chance”?

References

Bauman, Zigmunt, Fluidni život, Mediterran Publishing, Novi Sad 2009

Berardi, Franco “Bifo”, “Unheimlich: The Spiral of Chaos and the Cognitive Automaton”, e-flux, 2023

Gospodinov, Georgi, Vremensko sklonište, Geopoetika, Belgrade 2023

Lee, Pamela M., Chronophobia: on Time in the Art of the 1960s, The MIT Press 2004